La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Foto: Anna Jermolaewa

La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Foto: Anna Jermolaewa

La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Foto: Anna Jermolaewa

La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Foto: Anna Jermolaewa

La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Foto: Anna Jermolaewa

La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Foto: Anna Jermolaewa

La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Foto: Anna Jermolaewa

La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Foto: Anna Jermolaewa

La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Foto: Anna Jermolaewa

La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Foto: Anna Jermolaewa

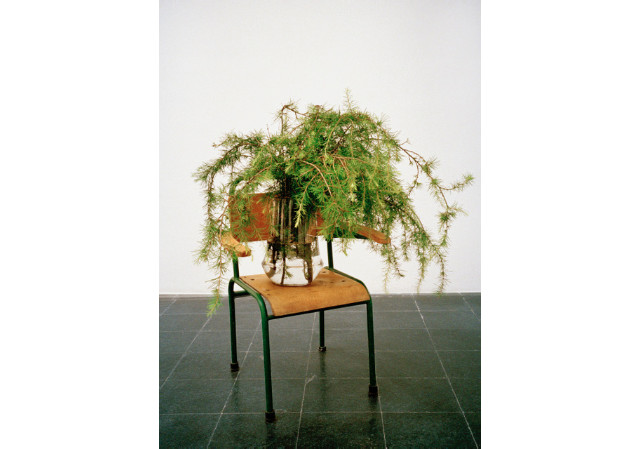

[...] Alongside such works in the characteristic style of documentaries, there are installations in which a media-effective political symbolism is concentrated in seeming objectivity, together with its photographic reproduction. In the context of an exhibition for the centenary of the October Revolution in St. Petersburg, Jermolaewa presented a series of bouquets: carnations, roses, orange branches, cedars, tulips, cornflowers, lotuses, saffron crocuses and jasmine (The Penultimate, 2017). Each of these plants is a color-symbol of a “revolution”. Beginning with the military putsch against the dictatorship in 1974, which the population welcomed with red carnations, „owers with positive connotations and an identifying color represent a regime change initiated by the people and usually running peacefully. The Carnation Revolution was followed in 2003 by the Rose Revolution in Georgia, in 2004 by the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, in 2005 by the Cedar Revolution in Lebanon and the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan and in 2007 the (unsuccessful) Cornflower Revolution in Belorussia. Also characterized as “color revolutions” by the international media were the Safron Revolution of 2007 in Myanmar, the Jasmine Revolution of 2010 in Tunisia and the Lotus Revolution of 2011 in Egypt. For Jermolaewa the flowers presented in the style of still lifes are a reminder of what political rulers like Putin most fear: an overthrow originating with the people. Together with Srđa Popovič, who founded the Center for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS), in 2012 she held a workshop on non-violent resistance and the role that art could play in it. Even in the internet age more is needed to achieve something politically than a mere click on a petition. Only the physical presence of many in real space creates pictures whose global circulation builds up the pressure that erodes out-dated structures.

Müller, Vanessa Joan: Anna Jermolaewa. Portfolio, in: Eikon, 2018, #101, S. 42 - 45

***

[...] Im Rahmen einer Ausstellung anlässlich des 100-jährigen Jubiläums der Oktoberrevolution in St. Petersburg präsentierte Jermolaewa eine Reihe von Blumensträußen: Nelken, Rosen, Orangenzweige, Zedern, Tulpen, Kornblumen, Lotusse, Safran-Krokusse und Jasmin (The Penultimate, 2017). Jede dieser Pflanzen steht für eine „Farbrevolution“. Angefangen mit dem von der Bevölkerung mit roten Nelken begrüßten Militärputsch gegen die Diktatur in Portugal 1974 repräsentieren positiv konnotierte Blumen und eine Identität stiftende Farbe seit dem Millennium meist friedlich verlaufende, vom Volk initiierte Regimewechsel. Der Nelkenrevolution folgte 2003 die Rosenrevolution in Georgien, 2004 die orangene Revolution in der Ukraine, 2005 die Zedernrevolution im Libanon und die Tulpenrevolution in Kirgisien sowie 2007 die (gescheiterte) Kornblumenrevolution in Weißrussland. Auch die Safranrevolution 2007 in Myanmar, die Jasminrevolution 2010 in Tunesien und die Lotusrevolution 2011 in Ägypten wurden von internationalen Medien als „Farbrevolutionen“ charakterisiert. Für Jermolaewa erinnern die stilllebenhaft präsentierten Blumen daran, was Machthaber wie Putin vielleicht am meisten fürchten: den vom Volk ausgehenden Umsturz. Gemeinsam mit Srđa Popovič, dem Gründer des Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS), hat sie bereits 2012 einen Workshop über gewaltfreien Widerstand und die Rolle, die Kunst dabei spielen könnte, abgehalten. Auch in Zeiten des Internets braucht es schließlich mehr als einen Klick auf eine Petition, um etwas politisch zu bewirken. Erst die physische Präsenz vieler im Realraum schafft jene Bilder, die über ihre globale Zirkulation den Druck aufbauen, der überkommene Strukturen erodieren lässt.